By Randy Gladman

The glorious invention of digital editing software and plasma flat screen monitors in the 1990s injected new life into Video Art, a previously anemic and fringe visual culture format that had always struggled to compete with Painting, Photography, and Film, its more alluring cousins. Though a few artists working with clunky, low-res televisions and analog recording technologies managed to contribute memorable masterpieces to the canon of contemporary art (Peter Campus and Nam June Paik are the obvious examples), these works belie the fact that early Video Art was challenging for viewers even when the most ‘advanced’ technologies were exploited. Prone to tape deterioration caused by mechanical friction, difficult to calibrate across environments, limited by awkward cabling and mounting structures, and subject to the basic constraints of simplistic image capture and weak audio fidelity, Video Art languished as the foster-child of the fine arts, largely ignored by major museums and provided shelter mostly by visionary yet funding-challenged new media galleries. Like Harry Potter living under Vernon and Petunia Dursley’s stairwell, this medium was skinny, self-confidence challenged, visually impaired, and underappreciated, ignorant of the magical power it would soon learn to wield.

The medium’s Hogwarts moment roughly coincided with the turn of the century and the arrival and mass-commercialization of high-definition flat screen televisions. Corresponding developments in digital editing software like After Effects and the Adobe Creative Suite programs unleashed new video editing, animation and visual effects powers previously accessible only to corporate, big-budget, Hollywood-style production studios. All of a sudden it became possible for artists working alone in their studios with non-existent budgets to render broadcast-quality Video Art. The only limitations were the bounds of the artists’ imaginations. The revolution would be televised after all.

Jeremy Blake is widely recognized as one of the first fine artists to successfully harness the seductive power of digital video editing software and high-definition monitors. Hanging plasma screens along gallery walls like so many canvases as early as 1998, Blake attracted attention for the manner in which he animated sequences of semi-abstract washes of colour to create digital videos that appeared to be living, breathing, moving paintings. His enchanting and innovative new media works exploring issues of violence, history, decadence, and fear, were included in important museum exhibitions like the Whitney Biennial (three times), incorporated into music videos for pop stars (like Beck), and used as emotional counterpoints in critically relevant cinema (as seen repeatedly in P.T. Anderson’s brilliant “Punch Drunk Love”). Tragically, in what was coined “The Golden Suicides” by Vanity Fair, Blake and his filmmaker girlfriend of twelve-years, Theresa Duncan, both killed themselves, one week apart, in the summer of 2007. Only 35 years old when he was last seen alive, naked and swimming out into the Atlantic Ocean from the shores of Rockaway Beach, Long Island, Blake had barely begun to scratch at the surface of an art form he helped yank into cultural relevance.

Nearly five years later, the genre of fine art pioneered by Blake and art stars like Bill Viola, Tony Oursler, Matthew Barney and Paul Pfeiffer is thriving, having earned an important role in the art marketplace and successfully surfing an unending wave of innovation in digital technology. At the forefront of the group of young, digitally-savvy visual artists working in Blake’s wake is Yorgo Alexopoulos. A friend of Blake’s in the last years of his life, Alexopoulos also worked briefly with him on a commercial project for Rockstar Games. Through Alexopoulos’ impressive commercial career producing visual effects for film and television (including visually stunning productions such as “The Kid Stays in the Picture” for which he was recognized at the Sundance Film Festival), he has developed leading-edge dexterity, expertise, and familiarity with the most current tools of digital animation and editing. His prowess with these technologies was exhibited recently in an epic installation in the lobby of the new Cosmopolitan Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas in 2010. Taking over the 432 LCD screens that sheath the eight massive columns in the hotel’s main lobby, his animated video “No Feeling Is Final; Redux” offered a massive and immersive environment and hinted at just how powerful and explosive this relatively new medium can be when harnessed with vision, control, and attitude.

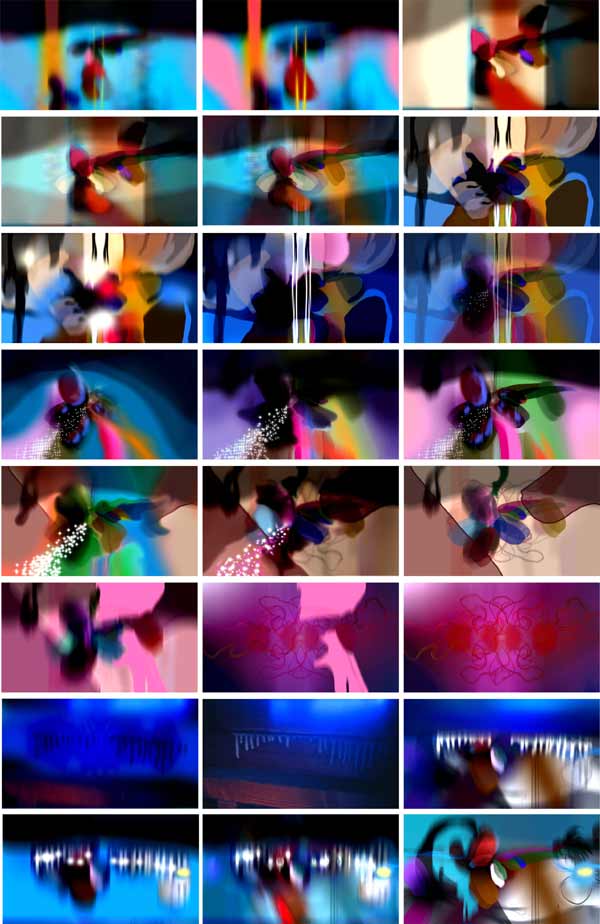

Transmigrations, currently on display at Cristin Tierney Gallery in New York City (February 16-March 31, 2012), marks Alexopoulos’s first solo exhibition in New York City in nearly 10 years. Continuing the precedent he set in Las Vegas, the artist uses multiple flat screens to create a plugged-in digital experience. This ambitious installation of 24 synchronized monitors explores magic, myth, and folklore, continuing Alexopoulos’ lifelong fascination with human belief systems that attempt to understand and codify a universe that is beyond comprehension. Transcendental, psychedelic, and electrifying, this work is most interesting for the way in which it elucidates the current state of Video Art in its most advanced and brilliantly enjoyable format. Seductive, definitive, colourful and accessible, this medium is no longer awkward and difficult to approach; as a mode of poetic communication, Video Art, in the hands of artists like Alexopoulos, has perhaps finally surpassed Painting’s ability to be compelling, relevant and gorgeous.

By Randy Gladman. Originally published in Artery, February 28, 2012.