By Randy Gladman

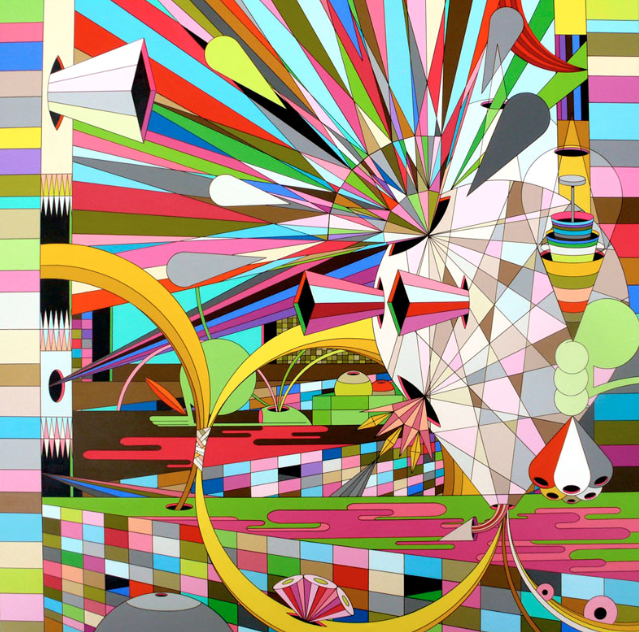

The website of the Southeastern Centre for Contemporary Art (SECCA) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, recently posted a six-minute long time-lapse video of the production of an onsite mural painted by the artist Dalek (James Marshall) and his team of assistants. Created for the exhibition North Carolina New Contemporary, Dalek’s vibrant and kaleidoscopic abstraction of video-game aesthetics slowly assembles in front of the camera lens to the beat of a jazzy soundtrack. As I watched the video this past Saturday night, with a touch of cabin-fever inspired by the Hoth-like Toronto winter outside my window, I thought about how great it is to see a deserving and brilliant Street Artist given time, space and resources by a museum, particularly one as charmingly off the beaten path as the SECCA. Here is more evidence, I realized, of the ongoing ascendance of the most important art movement of the new century.

The term “street art” has shifted in a positive direction over the past 10 years. This metamorphosis has been even more pronounced since the practical adoption of Shepard Fairey’s “Hope” posters by Barack Obama’s presidential campaign in 2008. Street art was once considered a societal infection that plagued beleaguered urban densities, but the mature examples of this visual art form have now invaded even the most holy contemporary museums and been championed by a new generation of collectors, curators and cultural commentators. Though many fine art periodicals have willfully or ignorantly displayed disappointing obliviousness to the importance of these young practitioners, an army of well-funded crossover magazines and websites have elevated these artists among audiences far hipper, more connected and massive than those the traditional art media enterprises can muster or interest. Possibly the current best documentary Oscar nomination of Banksy’s mind-twisting film Exit Through The Gift Shop will shake and awaken the upper levels of the art establishment from its slumber.

The pieces created by street artists like Banksy, Barry McGee (Twist), and Os Gemeos (twins Otavio and Gustavo Pandolfo), are not yet viewed as “blue chip”. This is because their collectors and strongest admirers are still exploring the outer reaches of their youth; the oldest of these supporters are generally still developing their successful professional careers and nurturing financial resources that are not quite ready to be deployed toward the serious aid of high culture. Just like all those before it, however, this generation, my generation, is on the march, driving tastes, and growing into influence. We are far more interested in the contemporary pop street artists whose points of references we share than in the current retinue of darlings promoted by the mega-galleries whose works are surely brilliant but not popularly compelling. By the end of this decade, our financial might will come to prominence, it will be our turn. When it comes to the visual arts, it will be street art in its gallery form that we will elevate. We have already begun to do so, but this effort is still nascent.

As the great street artists and their artworks enter public consciousness, it is imperative to note the direction of the movement. The museums and the market have come to street art, not the other way around. There is no sell-out here, no compromise. Though random, monikered, cowardly critics may claim otherwise and hurl accusations from the shadows of the blogosphere, these street artists have not “gone mainstream”. At least not the better ones. Instead, mainstream went Main Street. Just as cool new vocabularies and manners of speech ferment and ripen in rough urban quarters before they are appropriated and widely adopted by the middle-classes, the works of Shepard Fairey, C215 (Christian Guémy), Stephen Powers (ESPO), and a whole loosely affiliated brotherhood of artists are being soaked up from above. Any metamorphoses that occur do so within the DNA of the consuming masses rather than within the bloodlines of the creators. Even a cursory look at the current quality of daily street art interventions on the streets of Brazil, New York, Paris, London or Tokyo demands an acknowledgment that this folk-art form has never been as good as it is right now. When the street art photographer JR recently won the 2011 TED Prize without having to compromise anything about the way he produces or displays his work, any lingering relevance of the clumsy accusations of selling out evaporated alongside whatever doubt still existed regarding the cultural imprint and crossover appeal of these artists.

And is crossover appeal not eventually the truest measure of superior artistic achievement? While cerebral flexibility and opaque moral questioning are the hallmark of many intellectual artistic masterpieces that deserve museum protection and historical relevance, our most widely-valued artworks are those produced by the popularly agreed-upon pantheon of artistic geniuses. Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh will always be cherished above Matthew Barney and Paul McCarthy because they offer a way in for everyone, not just a minority with a fetish for obscure analytical discourse. From Jacques-Louis David through Andy Warhol, the great artists of any era are those who reflect culture with a popular mirror large enough for everyone to peer into, not just a self-selected slice of the population.

Because the medium used by street artists is the most public of all, namely our transportation infrastructure (streets, trains, tunnels, and bridges), their work is suckled from the very beginning by the impulsive need to transmit meaning to anybody and everybody, not just somebody. This is their greatest strength. This form of art is no longer relegated to the kids’ table; it is finally starting to take its well-deserved seat with the adults of high culture.

By Randy Gladman. Originally published in the Financial Times of London’s How To Spend It, February 7, 2011.