By Randy Gladman

‘Street Art’ exists in heavily urbanized environments from Tokyo to Toronto. Much of it is ‘graffiti’, that pestilence of territorial pissing by visually impaired half-wits who have little creative output beyond barely-literate scratches of their own names. However, an informed eye notices that the seas of scribbled spray paint, stickers and wheat-pasted billboards polluting the sides of buildings are sometimes topped by a foamy sprinkling of intelligent work that competes in the same public urban space. Barry McGee, a.k.a. Twist, whose wall paintings, drawings and mixed media installations were among the first to migrate from the streets into galleries such as Deitch Projects in New York and museums like the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum, is one of the best-known practicioners.

Shepard Fairey, whose Andre the Giant has a Posse stickers and Obey populist wheat-paste posters can be seen in settings from San Francisco to Singapore, exemplifies the multi-directional cross over of these artists into the gallery and into consumer products. Together with Brian James ( a.k.a. KAWS), Stephen Powers (a.k.a. ESPO), and James Marshall (a.k.a. DALEK), they comprise a movement of artists—coined ‘The Disobedients’ by Tokion magazine in May 2002—who use the aesthetics and distribution tactics of Street Art but cross breed them with a strange brew of Pop culture, illustration, commercial toy production, critical intelligence and artistic integrity.

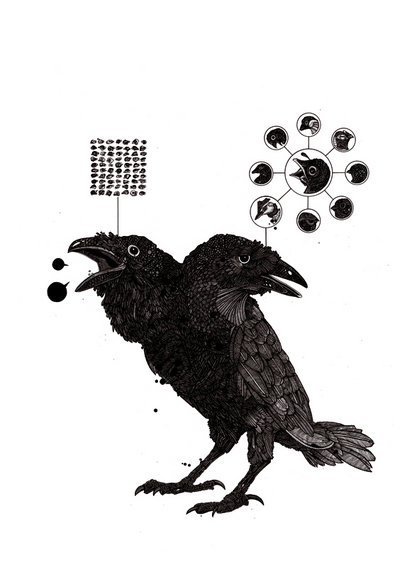

Nicholas di Genova, one of shamefully few talents to graduate from the Ontario College of Art and Design in 2004, readily admits their influence. In his debut solo exhibition, at Toronto’s tiny but edgy and inspiring Le Gallery, di Genova offered ink and ‘cell animation’ paint on mylar drawings that displayed his attention to artists like Twist, Futura, and DALEK. His nascent career has been noticed outside of Toronto and he has been included in New York City, Detroit, London, Berlin, and Singapore group shows, as well as Pictoplasma 2, a German collection of the best of international character design. Di Genova’s splotchy black outlines, flat fields of solid muted color, and clever suggestions of depth via mylar-and-Plexiglas sandwiches, show the important influence of Japanese anime and manga. At times his drawings look like they could come directly from the pages of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira manga with their intricate parallel linear shading, finely detailed outlines and gritty futurism. Unfortunately, the work has none of the narrative brilliance of Otomo’s epic Sci-Fi masterpiece.

Story and meaning are lacking. With silly titles like Lump-Head Triclops and Bi-Ped Fish Head Crabot, the works are loosely based on a post-apocalyptic/post-human world populated by mechanized mutations of animal species. However, it is a fanciful and naïve view that fails to deliver any significant message or social commentary. The sculptures included in the exhibit were also regrettable and cluttered the small gallery with objects that showed only that the artist has much to learn in three dimensions. Yet, di Genova’s style is confident and it forms an original departure from his influences. The huge library of charming characters that he has already created function as the foundation of a rich visual language, one that will enable him continue to participate in a vibrant, if underground, art movement.

By Randy Gladman. Originally published in Canadian Art, Vol. 21, No. 4, Winter 2004