By Randy Gladman

Walking into Ryan Humphrey’s solo show at Caren Golden Fine Art was like walking into Valhalla; a place where the holy relics of my childhood heroes retired for eternity. I’ve searched and searched for this place — this garden of delights where my boyhood toys relocated after Mom trashed them when I moved to college. I’ve ransacked her house so many times, disbelieving the fact that she turned over my Millennium Falcon to some infidel stranger who does not believe in the Force. Some poor sap who doesn’t understand the magnitude of Boba Fett in a galaxy far, far away.

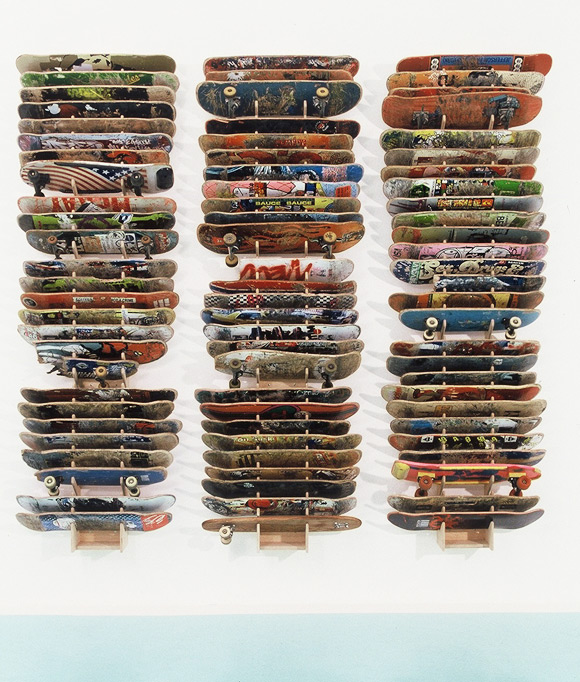

This exhibition is an American teenage boy’s wet dream. Star Wars action figures stand to frozen attention in two installations comprising a mishmash of materials; a photo mural of Earth seen from the moon provides a setting from which platforms extend supporting X-Wing starfighters and characters like Jabba the Hut and Yoda. Across the room, wooden BMX ramps Handmade by Humphrey curve up the gallery walls. To squelch any questions of how the footprints and tire scuffs got on the pristine white paint, mini video projection units placed between the ramps present Humphrey himself, on his tricked-out BMX, riding up the quarter-pipes at high speed. He makes tailwhips wall-plant attempts, one-handed wall-plants, wall-rides and decades look easy, still confident in the BMX skills he developed growing up in Ashtabula, Ohio, where as a teenager he was a sponsored amateur by brands brands like Vans and CW Cycles. Nearby, beautifully crafted models of late ‘70s Chevelles, Chargers and GTO’s gleam on handmade shelves in front of retro photographs of killer waves breaking on a shore. Filling the gallery with the shredding sound of Eddie Van Halen’s guitar magic, the subwoofer and twin tweeters imbedded in Six Steps to Enlightenment offer the ultimate in ‘80s cock-rock sensibility. Backlit CD copies of the group’s first six albums are mounted right into this installation and viewers are welcome to exchange Diver Down for Fair Warning in the CD player. Rock on.

A short stroll down the hall in the gallery corridor leads to a sculptural work called Scirocco Project Part 1 (Yang). Like a Transformer fighterplane that turns into a towering Decepticon robot, this vehicle has been transmogrified into a nutbar home theatre with audio and video. Bought as a parts-car for another Scirocco he is currently turning into part two of this project, Humphrey removed the engine, engine compartment, transmission, and front windshield before cutting the body into three lengthwise parts (so he could fit it through the narrow door of the gallery). Wheel-less and jacked up so viewers can see the bottom-mounted neon light illuminating the concrete floor below, this desiccated hot rod is set in the back room of the gallery where the walls have been painted with a stylized rock desert landscape perfect for Wile E. Coyete.

After figuring out that I was allowed in the vehicle, I climbed inside and chilled out on the cozy backseat and watched five television monitors installed where the front seats, dashboard and windshield should have been. The monitors projected scenes from Atari car-race games and retro car-race films like Smoky and the Bandit (1977) and Mark “Luke Skywalker” Hamill’s only other claim to fame, Corvette Summer (1978). Although the films are shown on mute volume, the band White Zombie offers the soundtrack while in the background the roar of hard-working horsepower cranking through stressed gears pumps out from hidden speakers.

The personal experience of having lived as an American boy in the ‘70s and ‘80s is the obvious common thread to these works. By using the iconology of pulpy Hollywood sci-fi, hair band rocker poetry, BMX exhibitionism, a Warholian sense of appropriation and a curious dose of gearhead machismo, Humphrey speaks to his video game-weaned generation in their own consumerist native tongue. But rather than finding these objects in a dusty attic and using nostalgia to create value, he rehydrates the cultural markers that defined his life to show their pervasive role in our cultural memory. Humphrey brings these materials drawn from our late twentieth-century folk traditions into the elevated space of the art gallery to map personal development through time and place.

The six Van Halen albums that provide Humphrey with the theme for Six Steps Toward Enlightenment mark the band’s progression toward the maturity they reached only with the departure of David Lee Roth; a development that stands in for the artist’s own personal evolution toward adulthood. For so many of us, the energy of the songs contained in these works contributed to our personalities, values, concepts of enjoyment, and attitudes at various points in the past. Humphrey asks us not to wax nostalgic about where we were and how we felt when we played these albums to death, but rather to understand the cultural contribution they have made. When I recognized the red, white, and black pattern painted on the artwork and made the connection to Eddie Van Halen’s famous guitar that popularized the abstraction in many music videos, I understood that Humphrey was commenting on just how deeply we have internalized the iconography of MTV culture.

The sense of familiarity songs such as Jump and Hot For Teacher provide is trumped by the Star Wars action figures in the two installations Ultra Geek (Trilogy) and Ultra Geek (Episode 1). Although he is alluding to the way many of us saw so-called icons in characters such as Han Solo and Chewbacca, Humphrey forcefully delineates our identification with the toys themselves. After initially questioning what these things are doing in an art gallery, my mind quickly shifted to scanning the diorama for figures I had in my own collection once, long, long ago.

These pieces allude to a vastly pervasive cultural phenomenon and an incredibly potent intimacy. I identified so thoroughly with these works that I found myself constantly reaching to play with them, only at the last moment remembering that they’ve since been injected with a ‘Do Not Touch’ art aura. Humphrey’s inclusion of these icons in the white cube of the gallery disorients this sense of ease normally associated with such familiar toys. He has rendered their extraordinariness, an importance we recognized while growing up but weren’t able to view through the hindsight light of critical awareness. These icons of late twentieth-century culture have likely already secured their place in the great museums of the future, but in such contexts they will not divulge the personal effects they had on the individuals who lived with and loved them. Humphrey’s layered and interactive installations delineate how we participated in these images, films, automotive obsessions, songs, toys and sports and how they helped us create, develop, understand, and enjoy our own personal identities as American boys.

By Randy Gladman. Originally published in Smock Magazine, Winter 2002.